The Best Job I Ever Had, Plus an Apology to Alfred Hitchcock

Paradise by the projection booth light

The best job I ever had does not appear on my résumé, though it’s hardly unique for mid-career folks like me to omit part-time work from their CVs. Nevertheless, as someone who eventually spent almost 15 years of his life teaching, researching, and writing about film, I see my senior-year part-time gig as a projectionist at the student union movie theater as a constitutive part of who I ultimately became.

At base, the job’s appeal was that someone paid me to watch movies — often good good ones, too. Sure, the pay was shit — $5.25 an hour, if memory serves —, but the labor-to-compensation ratio was quite high, and for what little work I actually did, I was wildly overpaid. To understand why this job demanded so little of me relative to other projectionists out there requires some historical context about film exhibition in general and the particulars of the University of Georgia’s Tate Theatre circa 2001.

I should also note that in the process of thinking back on my time in the booth for this essay, I excavated a buried memory of an ill-advised decision I once made late at night in a tiny recess of an empty campus movie theater. I shall hold that confession until the end.

A Brief History of Film Projection

The vast majority of movie houses today rely on digital projection. High-resolution video files are cued up on a computer, converted to analog, and projected onto a silver screen. Apart from preliminaries like adjusting the focus and dimming the lights, little is asked of the projectionist beyond hitting the “play” button. This is why most projectionists today have little specialized training and pull double-duty with concessions, ticketing, sweeping up, and the like.

But when actual analog film is screened, someone has to oversee a mechanical process whereby a motor pulls a strip of perforated celluloid from a reel, through a series of turning, toothed gears, stopping each 35mm frame in front of the lamp for 1/24th of a second. A lens blows that image up and outward so that it fills a screen exponentially larger than the postage-stamp sized film frame from which it derives. That basic process of getting an image onto a screen persisted more or less unchanged for over 100 years.

But what this description doesn’t account for is the length of the film in question. At the risk of bogging down in the weeds here or straining my limited facility at math, one second of film comprises 24 frames of 35mm film, which is approximately 1.5 ft. in length. That means that when you watch a two-hour movie in 35mm, just under 11,000 feet of film has to unspool through the projector in the cramped booth behind your seat. To put this into perspective, that 120-minute movie, laid end-to-end, would be the length of 36 American football fields.

Now, if all 11,000 feet of film were wound onto a single reel, that reel would have to be about 6.5 ft. in diameter. That’s feasible for neither lifting nor shipping. Thus, the bulk of my job, such that it was, was to take several small shipping reels of film and assemble them onto larger ones that held roughly 60 minutes’ worth of movie, about the maximum weight a top-mounted projector can tolerate.

For the bulk of film exhibition history, a feature-length movie greater than 60 minutes in runtime required either an intermission to allow the projectionist to swap reels at the one-hour mark, or the use of two separate projectors that could be swapped on the fly. Prior to the 1980s, most theaters, including the one that employed me, opted for the latter approach.

In this arrangement, the booth was outfitted with two identical projectors situated side by side. As the first roll dwindled down, the projectionist would watch for two “cue dots,” as they are called, in the upper-right of the frame. Perhaps you’ve noticed them before1:

And here’s how it would likely appear on the filmstrip itself:

At the sight of the first dot, the projectionist fires up the second machine; on the appearance of the second, they press a button that closes off the the light from projector #1 and opens the damper on projector #2. This procedure is called a “changeover,” and if synced and executed correctly, the transition is more or less seamless.

The two-projector system gradually receded from prominence with the rise of the suburban multiplex in the 1980s. With auditoriums numbering into the double digits, it hardly made economic sense for a single employee to babysit one or two screens at a time. Engineers responded to this inefficiency with the platter system. Instead of mounting the reels vertically atop a pair of projectors, the celluloid from the shipping reels was combined onto enormous reels laid on their sides, alleviating the weight issue that necessitated the dual-projector arrangement in the first place. Once the films were assembled onto single reels, they required even less attention since the manual changeover was no longer necessary.

But it also didn’t make sense for small, one- or two-screen theaters like mine at the Tate to upgrade their projectors to platter systems that were best suited to high-volume operations. This particular market reality proved quite the boon for me.

The Benefits of Repetition

The movie theater where I worked, at a flagship state college, operated much like the American public broadcasting model — in the red, for public edification, outside of commercial pressures. Weekday screenings tended towards art-house movies, foreign cinema, indie films, or Hollywood classics. Popular, second-run fare and midnight screenings of cult movies were typically reserved for the weekends.

But because of this single-screen, two-projector setup, pressing that changeover button, rewinding the reels, and re-threading the projectors was the only real work I would perform during a shift — no more than 20 minutes of labor per screening.

The biggest perk of all that down time was that it allowed me to study — not my coursework, mind you —, but the films I was tasked with exhibiting. I’d watch the first screening like any other patron, hopping out of the booth and taking it in from the auditorium with an eye towards plot and character. For the second screening, I’d zero in on editing, camera work, and the finer points of mise-en-scène. As with the bat-shit video store of my youth, I had found myself in yet another circumstance conducive to voracious movie-watching.

Every day at work offered an opportunity to sharpen my critical faculties. It felt like a gift having my maiden voyage with Mulholland Drive (2000) on a big screen and then getting three more cracks at dissecting it in a single weekend. Watching the same movie back-to-back became a commonplace and critical component of my film education.

Shifts generally ran five or eight hours, depending on if it were a weeknight or weekend run. And because it was in the student center, I would occasionally sneak friends in through the backdoor to watch movies unticketed, saving them the exorbitant $2 entry fee. Others would pop in to hang out in the booth on the way to and from classes.

My friend Jay would even ride with me to work so as to intentionally strand himself at the student center.2 He’d catch the first screening of the day and then, on account of his temporary self-marooning, study until my shift concluded. That was the stated goal, at least. More often than not, he ended up in the projection booth with me, shooting the shit or executing the changeover in my place. Though not at all difficult, there is a certain pleasure in nailing the timing. And I was glad for the company.

The Scene of the Crime

Some of the movies I got paid to see, and re-see, that year include Mad Max (1979), Waking Life (2001), Monster’s Ball (2001), Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), Fargo (1996), and Barbarella (1968). Tough gig, huh?

For one night only, I also got to project a newly-struck, never-before-screened 35mm print of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). To this day, I don’t know how or why our little theater ended up with such a pristine print.

How do I know it had never been screened before? Recall that part of my job was to assemble the film from the shipping reels onto the larger feed reels. This involved cutting off the excess “head” and “tail” of the film strip from each reel then “splicing” the rest together with tape, like so:

This also means that over time, a circulating film print will accumulate a thick surplus of tape at the beginning and end of each shipping reel. If you see no tape, you’re probably holding a virgin print. I was the first person to ever take a blade to that particular physical copy of Psycho.

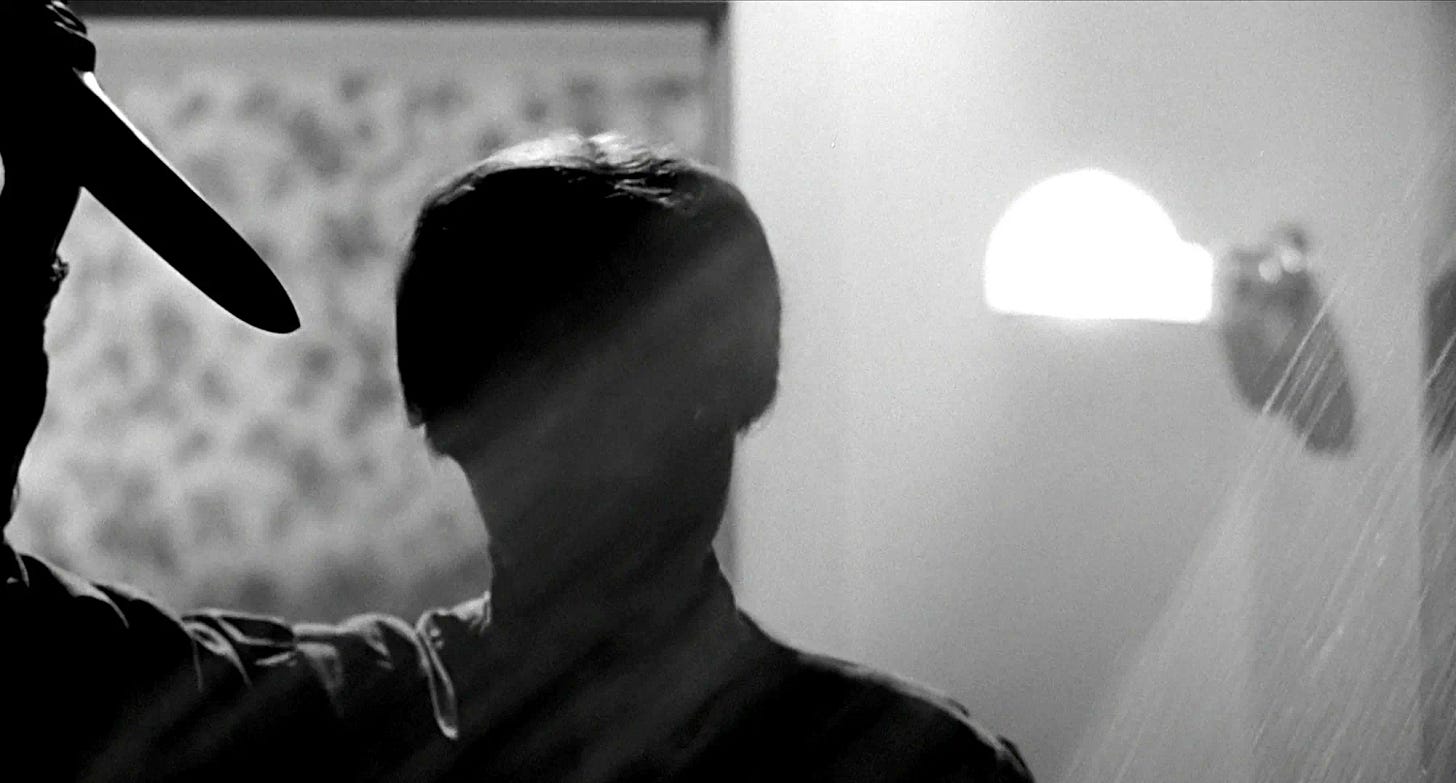

Now, even if you’ve never seen Psycho, you are likely familiar with the famous shower scene. Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) is interrupted in the shower by a murderer with a kitchen knife, and to convey the violence of the act without depicting the gore or Leigh’s nudity (or the killer’s identity), Hitchcock utilizes myriad camera angles and cuts over a short burst of about 45 seconds to replicate the thrusts of the knife and the brutality of the attack. All the while, Bernard Herrman’s score, with its shrieking, staccato violins, is likewise fractured and piercing.

It is a matter of some debate as to exactly how many shots comprise this scene, especially since some of them are on screen for fractions of a second, sometimes as few as two or three frames. But as the projectionist, I got to watch the film closely — and I mean the literal, physical filmstrip itself. On a pristine, unsullied print, I was able to analyze one of the most acclaimed scenes in all of cinema history frame by frame.

I am not proud of this next part, dear reader. It is a shame I have carried with me for more than two decades. At the end of that night, while spooling the film back onto its shipping reels, I stopped and reviewed the shower scene one last time. And then I did it: I cut a single frame from the strip, put it in my wallet, and then spiced the remainder back together. It was a frame roughly corresponding to the moment seen is this digital screen grab:

For years, I have rehearsed my defense in the event that I am ever tried for my crime against cinema. It goes like this: my back-of-the-napkin math suggests there are just shy of 157,000 frames in a 35mm print of Psycho. I absconded with but one, a mere 24th of a second! No one would possibly notice its absence, especially in a scene composed of so many shots and cut so rapidly. No reasonable person could argue that I’d altered the film in any appreciable way.

But no matter how much I try to convince myself of my own argument, I can’t commit to it. For I know that there were countless other projectionists after me, like me, who delighted in the beautiful print that had found its way to them, and who held up the film strip to the light to study this scene — this all-timer of a film-nerd scene! — and in the process discovered the telltale adhesive evidence. It is not uncommon for film strips to break, and sometimes small sections of film are damaged or lost as a result. But for that splice to be there, in that specific spot, in that particular scene, strains credulity. Sure, no one could trace the crime back to me, and even if they could, what’s the statute of limitations on frame-stealing? Furthermore, my punishment is knowing that they know that one of their own, a fellow projectionist, had broken the unwritten but universally understood rule prohibiting the desecration of film prints.

Plot twist: I eventually lost that purloined frame. With a half-dozen or more apartment moves over the years, something so small, so delicate, was certain to one day disappear.

Being a projectionist was the best job I ever had — and, alas, I wasn’t worthy of it. But if the powers that be wanted someone both morally upstanding and willing to work until 3am on a Friday, perhaps they should’ve come off of more than $5.25 an hour? I digress. Suffice it to say, though, that I regard the decade in which I taught film in exchange for meager graduate stipends and lived precariously off the tenure track as penance for the misdeeds of younger, dumber self. I can only hope Hitch — and whoever operates that great celestial projection booth in the sky — will forgive me my indiscretions.

The shot comes from Fight Club (1999), which explains the mechanics of a changeover to set up the protagonist’s habit of about placing subliminal frames of pornography in children’s movies. I resisted the urge to use this as an example given my reluctance to participate in David Fincher film bro-dom — even if I do like Fight Club and several other of his movies.

Before age took his hair, Jay looked remarkably like Kevin Bacon, a resemblance he refuses to acknowledge and, frankly, resents. I shan’t post his picture here, but please know that I revel in the fact that this footnote will likely make him squirm.