In light of the recent 30th anniversary theatrical re-release of Seven in IMAX, I wanted to re-up this post that I first released a year ago. I keep fighting the good fight.

Good people of the jury,

I know it is a matter of custom to address you as “ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” but my aim is to be as inclusive as possible. If we were speaking in a less formal setting, I’d address you by whatever names you wished to be called. If you were born Charles but go by Chuck or Chip? Say no more! Likewise, if you prefer they/them pronouns, I’m more than happy to oblige. You dislike gendered or credentialed honorifics like Ms. or Madame or Doctor or General? Hey, we’re all friends here!

The Defense would advocate for this same linguistic flexibility with regards to their client, but I’m here to tell you why you mustn’t.

Disregard spelling for the moment and hear this word: “Seven.” That’s the title of David Fincher’s 1995 serial killer thriller. Were we to take that word, that title, and render it in written language, it would appear as “s-e-v-e-n,” or perhaps simply as the numeral 7. Nothing to quibble with there. But the Defense will attempt to convince you, for some godforsaken reason, to blend those two written forms of a straightforward word and write it thus: “s-e-7-e-n.” Why?

Exhibit 1, Your Honor: a screengrab from the title sequence of the film in question.

“It’s the official title of the movie,” the Defense will say. “It’s right there in the opening credits!” But is that truly the movie’s sanctioned, legitimate title, or merely a stylization thereof? You see, this is a matter of some debate, and I think we should look outside the film itself to resolve this controversy once and for all.

I enter into evidence Exhibit 2: the original poster for the movie from around its U.S. release in September of 1995.

Note that here, unlike in the opening credits, the title is rendered exactly as it is conventionally spelled — though in lowercase. (We will return in a moment to the matter of capitalization.)

Members of the jury, I’d also like to draw your attention to a second notable aspect of this poster. If it pleases the Court, Exhibit 3: a zoomed-in image of the credits from the bottom of the poster.

There again, you’ll note the title: Seven. We have ourselves a discrepancy between how the title appears in the film itself and how it appears in marketing materials. So what’s the real title?

One thing is for certain. In the aftermath of the movie’s release and the long tail of its success, some critics and fans seemed to have resolved that Se7en is unquestionably the correct appellation. But this is a court of law. Jurors like yourselves will decide this issue, not the court of public opinion. So let’s keep digging.

Exhibit 4: the official press kit from New Line Cinema, which was provided as a resource to critics and journalists in advance of the movie’s release. The title therein: Seven.

Perhaps you are noticing a trend. But wait: there’s more. Exhibit 5: The first draft of screenwriter Andrew Keven Walker’s script for the film, taken from his very own personal website. You’ll see that it is clearly titled Seven.

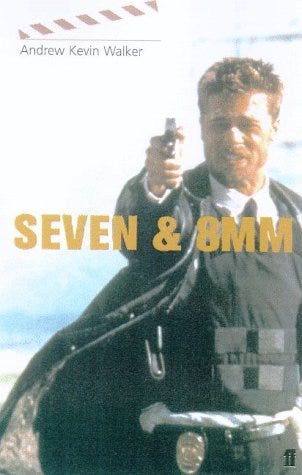

I also wish to enter into evidence Exhibit 6: Faber & Faber’s 1999 publication of Walker’s screenplay. Again, Seven is the title.

So fans and the opening credits call it one thing, but the screenplay and marketing collateral and ancillary products call it another. More research is in order. Let us consult a third authoritative source. The preeminent trade association within the movie industry is the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences. Jurors, you might be more familiar with the organization’s annual Academy Awards, or The Oscars as they are informally called. Mr. Fincher’s picture, or more precisely, its editor Richard Francis-Bruce, was nominated at the 66th Oscars in 1996 in the category of Best Film Editing. Entering into evidence Exhibit 7: the Academy’s list of nominees and winners from that ceremony, archived at its official website. You’ll notice that there is no numeral in the title.

It is also instructive to look elsewhere on that list, namely, at the category for Art Direction. Two other nominated films concern us here: Richard III, rendered with Roman numerals, and Apollo 13, with Arabic. Clearly, the Academy is not using its own in-house style guide for the treatment of movie numerals; rather, it defers to the films’ official titles.

Let’s recap this briefly: Seven is the preferred title in the film’s screenplay; its press kit; on its poster, twice!; and at the Oscars. It’s all quite compelling when taken as a whole.

But set aside authoritative sources for the moment, good people of the jury, to consider the logic behind departures from convention in movie titles. A notable example from 2022 is the campy horror film M3GAN. The curious spelling and capitalization is owed to the titular homicidal doll’s name, which the movie tells us is an acronym for “Model 3 Generative Android.” The use of the numeral in the title as well as its capitalization are thus linked to and motivated by the narrative. Ditto for an earlier film, S1m0ne (2002), about a synthetic actress that shares with the movie a name derived from the R&D descriptor “Simulation One.” It even playfully integrates the 1s and 0s of binary code.

Against these examples, we can see just how illogical the hybrid Se7en is! What thematic purpose could the number serve if it is merely reiterative? Not only that, but the numeral 7 and the letter V, as glyphs, do not resemble one another visually, even if they would be similarly constituted in terms of pen strokes.

Moreover, folks, we are quite accustomed to swapping numbers and letters in a variety of settings, such as vanity license plates — alphanumeric by law in some U.S. states — and password security best practices. In such contexts, a 5 bears an iconic resemblance to an S, and likewise for 4 and A and even 3 and E. We have a mental framework, a cognitive schema, for stuff like this!

Then there is the question of capitalization. One most often sees the alphanumeric rendering of the Fincher film as such: Se7en. Yet, recalling Exhibit 1, in the credit sequence that fans often take to be dispositive evidence of the work’s official name, all characters are capitalized (SE7EN). If those credits are the final word on the title, then shouldn’t it always be rendered in uppercase? Rarely is that the case in popular discourse.

Exhibit 8: And by this same logic, wouldn’t Fincher’s first movie, from 1992, be spoken of as “Alien Cubed” on account of the superscript 3 in both its credit sequence and marketing? Jurors, you’d be hard pressed to find a single case of that anywhere.

Now, Seven is hardly the only movie with nonstandard spelling, irregular capitalization, or unusual stylizations. A particular David Cronenberg sci-fi film from 1999 comes to mind. The movie opens in a focus group where marketing gurus actively discuss the stylization of the title for a new virtual reality video game called eXistenZ, a play on the word “existence.” Cronenberg cleverly redeploys that as the title of the film, the subject of which is worlds within (virtual) worlds. As with M3GAN, the deviation from convention is justified within the logic of the movie. We cannot say the same for Fincher’s.

So we’ve established that Seven is the film’s official title, that the stylized variant is “unmotivated” with regard to the narrative, and that the impulse to honor the title that appears in the opening credits is selectively or inconsistently applied.

But despite this, the incorrect title has become so popular that it has largely unseated the proper moniker. Indeed, the Internet Movie Database, often regarded as the authority on such matters, lists, and therefore endorses, the alphanumeric version.

Upon Seven’s release, there were stray reviews here and there referring to it as Se7en — one even openly condescends to its readers as it does1 — but the overwhelming majority adhered to the correct title. What changed in the intervening years?

The film’s distributor bears part of the blame. As the movie grew in stature, New Line Cinema began using the stylized title for each new DVD and Blu-Ray edition. Let the record show that the first to do so was the 2000 Platinum Edition.

So did audiences begin calling the film Se7en because of a principled commitment to treating the title presented in the opening credit as gospel? Nope. See: “Alien Cubed.” Then perhaps it’s because the film’s stature only grew over that time, and the DVD was one of the primary means by which people encountered the movie?

Or might not it be the other way around? Might it be that the film’s fans embraced the hybrid title and the distributor responded in turn?

I respectfully submit that the latter is the case, though I cannot prove it definitively. Members of the jury will recall, though, that this is a civil trial, where the burden of proof is the preponderance of evidence, not guilt beyond a shadow of a doubt.

My theory is that technological change played a role. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, from 1997-2000, the number of U.S. homes with internet access more than doubled. By the time Seven’s Platinum Edition hit store shelves, 52% of Americans regularly used the web.

It would seem that as cinephiles congregated online in Usenet groups and IMDb forums, the alphanumeric title slowly took hold. Exhibit 9, Your Honor: Google search trends between 2004, the first year such data is available, and 2011. Jurors, please note the upward trajectory of “Se7en.” It didn’t hit critical mass until 16 years after the film’s debut!

This window of time was a fruitful one for movies like Seven, as several other Dark, Gritty, Morally Gray (TM) films attracted viewers, especially young men: The Usual Suspects (1995), Fincher’s later Fight Club (1999), and practically all of Christopher Nolan’s output from Memento in 2000 to The Dark Knight in 2008. It even extends to the recent Joker (2019), where a second actor won an Oscar for playing the painted lunatic in a span of only 11 years.

Oddly enough, this same batch of movies remains popular today among the very same demographic. It’s as if each generation of high school and college dudes discovers and champions these tales of sociopathic killers and nihilistic violence. Cultural critics have even coined a term for the subset of young men who gravitate towards this pantheon of toxic masculinity: Film Bros.

However, long before a name crystalized for this cohort, Film Bros were championing their canon and waging, through persistent usage and weaponized “well, actually” mansplaining, a decentralized, uncoordinated campaign to turn Seven into Se7en.

May it please the Court: Exhibits 10 and 11: tweets from insufferable fanboys regarding the film in question:

History tells us that the longest conflict in American history was the War in Afghanistan, but members of the jury, this is incorrect. Actualllyyyyy, the war to usurp the title of this film with its silly variant has continued unabated for more than 34 years, and I fear there is no end in sight.

The crime here, such that it is, is not a matter of taste. Hell, I like some of these movies myself, and who am I to tell others what they should or should not enjoy. Rather, the sin of it all is the Bros’ slavish devotion to a presumed authorial intent. You see, at their core, Film Bros are nothing if not committed auteurists, deifying the directors they regard as Artistic Geniuses and Cinematic Trailblazers, men — and it’s always men — of astonishing technical command and philosophical depth. But this artistry is self-evident only to them, and those outside their ranks need desperately for the Bros to decode it for them.

Exhibit 12:

Film Bro sycophants insist that Seven is Se7en because they treat any and all deviations from the norm as Easter eggs, clues, or directives. The title that appears in the opening credits of Seven surely couldn’t be a stylization of an otherwise straightforward name, for while your average director is playing checkers, David Fucking Fincher is playing chess.

Rest assured, members of the jury, that not everyone who uses the Se7en moniker is a Film Bro — their campaign has been a success, alas — but every Film Bro damn sure calls it Se7en.

The crime of Film Bro-dom is not one of taste; rather, it lies in its obsequiousness. Good people of the jury, you must return a verdict of guilty for this exasperating idolatry. The Prosecution rests, Your Honor.

“Pedants take note,” writes one critic in a contemporaneous review, “the title is actually spelt Se7en.”

![Twitter user @hicksimon writes "It's raining like its [sic] the movie Seven." @GeraghtyDarren replies "Actually the title is 'Se7en.'" Twitter user @hicksimon writes "It's raining like its [sic] the movie Seven." @GeraghtyDarren replies "Actually the title is 'Se7en.'"](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!O086!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ffad6ae77-dcb7-4486-9a73-13d407038609_485x236.png)