On Escaping: 'Dazed and Confused' (1993)

How is it that Richard Linklater's depiction of 1976 Austin reminds me so much of rural Georgia in 1995?

I.

In 1995, we had it down to a science, Dave and me. Following a home football game, we players often wouldn’t leave campus until after the local cutoff for alcohol sales. This meant we had to take the proactive step of securing our post-contest beer in advance, during the 30-minute window of free time after the last bell of the school day and before our locker room call-time.

The only convenience store in town that accepted my janky, homemade fake ID was 17 minutes roundtrip from our high school, thus leaving little time for proper storage. Instead, we had to stash the beer in the trunk of my car, un-iced, in the late-summer/early-fall Georgia heat. We’d learned, though, that all it took was eight minutes and two bags of ice to take domestic light lager from a near-boil to a tolerably drinkable temperature.

Then, with nominally cold beverages in hand, we began the repetitions: of sips, of Sublime’s 40oz. to Freedom (soup to nuts), of loop after loop driving through the “central business district” of Waynesboro, Georgia.

II.

Dazed and Confused (1993), Richard Linklater’s second feature film, is noted for its looseness. Willing to simply “hang,” it forgoes conventional narrative drive in favor of a drifting, ambling interest in its sizable ensemble. In that spirit, what follows shall too meander.

Set in 1976 Austin, Texas, on the last day of school, Dazed and Confused debuted in 1993 to mixed reviews and pitiable box office receipts. It was an inauspicious start for a film that has only grown in stature with each passing year. Today, Dazed and Confused routinely lands on the lists of movie superlatives (e.g., best teen movies, greatest cult classics, among the best films of the 90s and even of all-time), and it helped launch the careers of future Oscar winners Ben Affleck, Renée Zellweger, and an indelible Matthew McConaughey, who folds the movie up, sticks it in his pocket, and walks away with it.1 Seemingly, the Venn diagram of McConaughey, the man, and his character Wooderson, is but a single circle.

Upon the release of Dazed, film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum called it “a better-than-average teen movie but not much more,” but within four years, he had changed his tune:

One of the key experiences for American teenagers of my generation was driving with the radio on and feeling the intoxicating effect produced by the marriage of rock music and the landscape passing by. This poetic, technological ritual […] finds a perfect cinematic crystallization in Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused, a film that gets better every time I see it.

Unlike Rosenbaum, I was on-board from jump. I rented the movie not long after it was released on VHS in 1994, and it took only one viewing for me to declare it my favorite film. Until that day, never had I finished a movie, immediately rewound the tape, and started it again. I watched it three more times over that weekend rental period. Within a week, I had purchased a copy of my own, one I thrust into the hands of nearly every friend in my circle, insisting: You have to watch this. To date, I have seen it more times than any other movie, easily upwards of 100. I can still recite every line.2

Despite taking place a full four years before I was born, Dazed felt instantly familiar to me, a teenager in mid-90s rural Georgia. To my mind, it wasn’t a period piece so much as a mirror that reflected back my own life — albeit with cooler cars.

Much about Dazed and Confused was recognizable to me and my peers. The mobile party that is a pick-up truck — driven not just by the teen boys but the young women, too — with coolers and beach chairs in the back; the local cops who do not arrest law-breaking players but enlist the head coach to mete out discipline instead; the Confederate iconography that was present then, in ‘76, and in my youth, in ‘94, and, thankfully, less often today: the high school’s namesake, Robert E. Lee, and the rebel flag sticker seen inside a locker.

But more than anything, the most resonant aspect of the film for me was how much of it transpired in, around, or moving between automobiles.

III.

1.8 miles is the distance between Dairy Queen, on the south end of Liberty Street, and McDonald’s, on the north, which mark the beginning and end points of my hometown’s main drag. The parking lot between a gas station (still there) and a Mexican restaurant (now a Chinese buffet), though not quite the physical midpoint of this stretch of road, was the center of the town’s social world.3

There the cars and their occupants would congregate to loiter — until the police broke up the crowd — or simply to park one vehicle and hop into another. If your ass touched only one car seat over the course of an evening, you were doing it wrong.

IV.

Linklater once described Dazed as the antithesis of a John Hughes movie:

I don’t remember teenage being that dramatic. I remember just trying to go with the flow, socialize, fit in and be cool. The stakes were really low. To get Aerosmith tickets or not? That’s a big thing. It was really rare when the star-crossed lovers from the opposite side of the tracks and the girl gets pregnant and there’s a car crash and somebody dies. That didn’t really happen much. But riding around and trying to look for something to do with the music cranked up, now that happened a lot!

That’s not to say, though, that nothing happens in his film. Much of its first third involves the rising seniors’ plotting and executing hazing rituals for the incoming freshmen class. The elder young women force their younger counterparts to “air raid” (that is, drop to the ground) upon command while being tarred-and-feathered with foodstuffs like condiments, flour, and oatmeal; meanwhile, the senior men mercilessly whip the freshmen boys with paddles fashioned during woodshop class.

It’s noteworthy, though, that the star quarterback and the film’s ostensive main character Pink (Jason London), who at one point recounts his freshman victimization, appears not to participate in these rituals as a senior. Yet with beer in hand, he spectates the frosh girls’ torment and does not intervene in the boys’. The same goes for the cerebral Mike (Adam Goldberg) and Tony (Anthony Rapp), who like Pink do not engage in the paddling but bemusedly watch the air-raid humiliation nonetheless. Mike even says the quiet part out loud: “What’s fascinating is the way not only the school but the entire community seems to be supporting this, or turn their heads. [The senior girls] apparently have permission to use the parking lot, and no parents seem to mind.”

More so than the hazing, it’s this sentiment of tacit approval from adults that calls to mind my experience of rural adolescence. In our case, the parental blind eye was turned not so much towards the unseemly behavior as it was to the notorious place in which said behavior was unleashed. More often than not, it was a place many adults in our lives had once frequented as well. But we nor they ever talked much about it.

V.

The characters in Dazed are nothing if not transient, moving from school and home to Top Notch and the Emporium and back again in a loop. The only time the majority of them come to rest at a single, common location is late in the film at the Moon Tower, the wooded site of their enormous keg party (or “beer bust” as they call it).

Waynesboro had nothing approximating Austin’s historic and iconic moonlight towers, though we youth did organize similarly impromptu and clandestine, if significantly smaller, soirees in cotton fields.

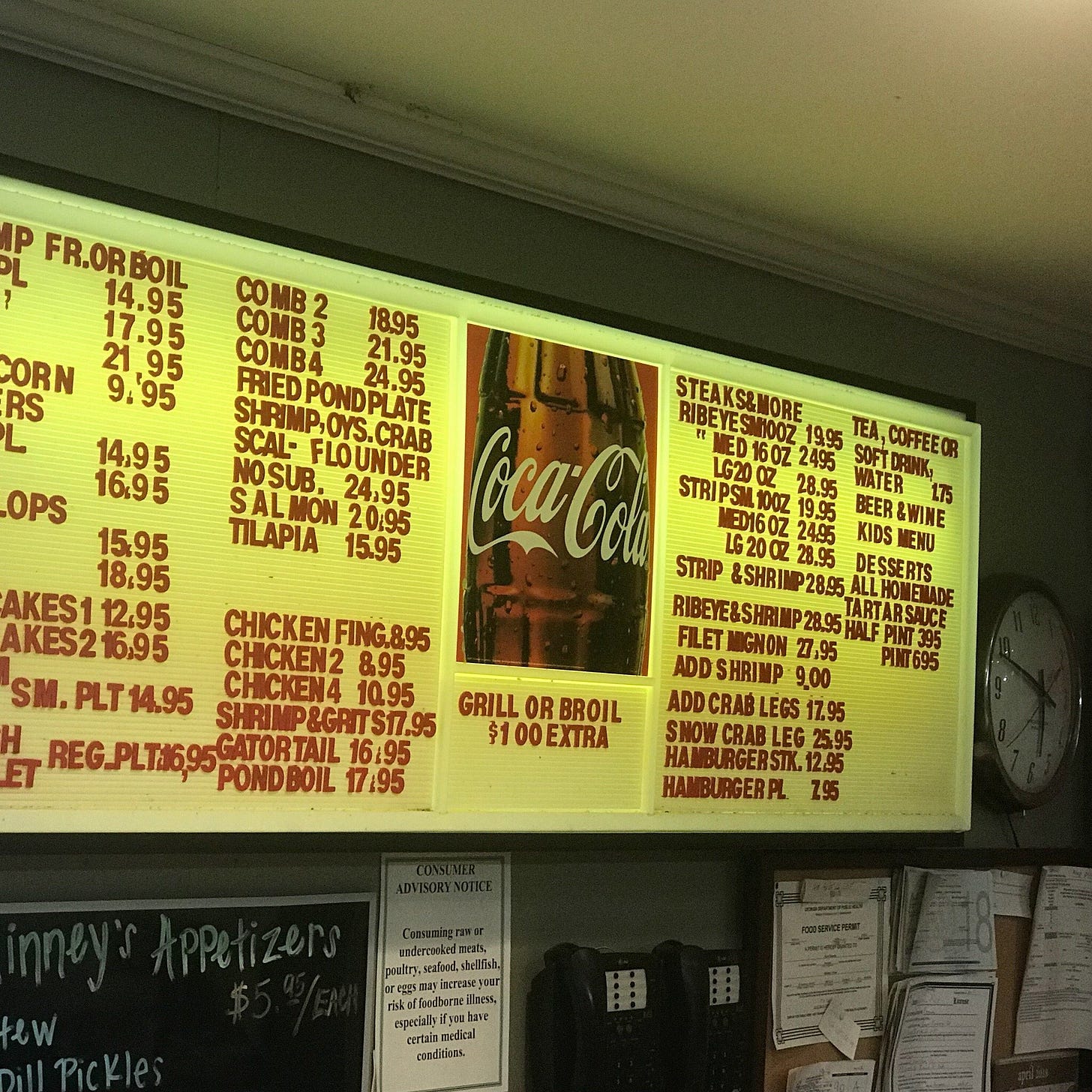

For something approaching the scale of Dazed and Confused’s notorious beer bust, one had to drive 30 miles south to Midville (pop. 385) and McKinney’s Pond. McKinney’s was the sort of fish camp restaurant serving fried catfish and bream one sometimes finds in pockets of the rural south.4 But McKinney’s also had a defunct skating rink on the property that the owners repurposed into a concert hall for regional touring groups.

Despite being in such a remote location, it landed notable acts like Percy Sledge, The Tams, George Jones, and The Drifters. And when the multigenerational beach music group The Swingin’ Medallions came to town every three or four months, it was a fucking event, drawing folks from all over a hundred-or-more mile radius from this backwoods music venue.

The Medallions had a radio hit with “Double Shot of My Baby’s Love” in 1966, and they (or their progeny) have been playing southern towns and shag festivals ever since, often in matching t-shirts and gaudy pants. Beach music was big in my part of the world, thanks in part to our proximity to South Carolina coastal town Myrtle Beach, the epicenter of the genre in the 50s and 60s. This music was omnipresent when I was a kid, a taste inherited from one’s parents and grandparents that was rekindled with the release of the Myrtle-set romantic comedy Shag in 1989. As a result, the mid-90s McKinney’s crowd that turned out for a boomer nostalgia act like the Medallions was incongruously dominated by college students and teenagers.

I can find no official capacity for the venue, but I’d guess the room held 300-400 people. But like a college football tailgate, the number of people outside the venue often rivaled that inside.

Thinking back on those Swingin’ Medallions shows, I am reminded of Mike’s appraisal of the hazing spectacles in Dazed: no one — not parents, police, or government officials — seemed to mind what transpired in and around McKinney’s Pond, and it leads one to wonder if they didn’t implicitly sanction it.

The security staff was comprised of off-duty law enforcement, even though it was apparent that all laws were temporary suspended when the Medallions were in town. Because of local liquor ordinances, the venue was strictly B.Y.O.B, and I can only assume this is why no one was carded upon entry. McKinney’s, at least on Medallions’ nights, was like an amusement park for underage drinking. Perhaps out of blind-eyed deference to the limited economic boon that McKinney’s was for Midville and surrounding communities, no one batted an eye at 15- and 16-year-old kids slamming cans of Bud Light and bottles of Zima.

Nor did they seem to mind that which accompanied such youthful imbibing: some vomiting, some fighting (usually broken up by the participants’ friends so as to not force security’s reluctant hand); and more than a few people groping one another on the dance floor, behind a tree, or supine in the bushes. As my friends Jason and Will, who hailed from another neighboring town, once noted, every Medallions show saw at least one broken engagement after one person or the other was caught dancing or making out with a stranger.

It strains credulity that McKinney’s hallmark permissiveness was some new development that evolved from a more buttoned-up past. Our parents, aunts and uncles, and teachers, many of whom were likely former attendees themselves, had to have known what transpired there. Perhaps they, like the unseen adults in Dazed and Confused, tolerated a bit of Dionysian disinhibition?

VI.

I have an uneasy relationship with my home town. I remember it fondly despite having always felt out of step with it, constrained by it. As a teenager, I was so keen to leave it behind that I started college early, moving to Athens a week or two after graduating from high school. And ever since my parents retired to North Carolina 15-some-odd years ago, I haven’t been back.

Material Ghosts was mounted to reconsider important movies from my past, but this retrospection has led me back to Waynesboro more often than I could’ve anticipated. When I sit down to write, I find myself gravitating to the place of my youth and compelled to write about it. If that limits the potential audience for these essays, so be it.

Part of the reason Dazed and Confused so resonated with me as a kid was that it spoke to some of my ambivalence about the place where I grew up. For much of its runtime, Dazed exhibits a tone that is at once comic and critical. It seems to like the characters inhabiting its world even while being repelled by the strictures and structures of a then much smaller Austin, one that feels closer to my hometown than the booming tech sector hub it is today.

Nowhere is Linklater’s conflicting affection and dismay with Austin more apparent than the late scene late where a handful of friends sneak into the football stadium at night to get high on the 50 yard line. There, Pink’s complaints about the town and the school and all the external expectations placed upon him are challenged by his peers. How can he act as though he is oppressed by this place when he’s had more fun than anyone should rightfully expect, when he practically runs the school and does as he pleases? To this he replies, “If I ever start referring to these as the best years of my life, remind me to kill myself.”

In what amounts to something of the film’s mission statement, Don (Sasha Jenson), resting his weary, drunken head on his girlfriend Shavonne’s (Deena Martin) lap, offers this rejoinder: “I just wanna look back and say, ‘I did the best I could when I was stuck in this place, had as much fun as I could when I was stuck in this place, played as a hard as I could when I was stuck in this place.’”5

Perhaps it’s this spirit that I’ve been returning to and that I find in places like the bacchanals at McKinney’s. To sum it up in words is to grasp the sheer oddity of it all: teenagers staggering around the grounds of a former skating rink as a facsimile of a 60s one-hit wonder plays beach music along the banks of a muddy pond in a landlocked town in middle-of-nowhere Georgia. I and my friends, given to youthful misadventure and open to the absurdity of it all, wrung as much as we possibly could out of our little town, even if they, unlike me, they didn’t feel themselves to be stuck there at all.

The term “nostalgia” is often misused to suggest simply thinking back fondly on the past, when in fact it implies a certain romanticized view whereby all that was pleasant is celebrated as the “good old days” and that which is less so is pruned off from memory and forgotten. To be nostalgic is to yearn for a past that is no longer recoverable and likely never existed in such a form in the first place. With that nuance in mind, I argue that this project, though focused on the past, is not nostalgic. I am not remembering only the pleasure at the expense of the pain. If anything, writing here is helping me to surface memories and see that the places I longed to escape are in some cases more interesting and more unique than the ones to which I fled.

You can get each new issue of Material Ghosts delivered straight to your inbox by becoming a free or paid subscriber via the button below. If you know others who might enjoy Material Ghosts, be sure to hit the “share” button.

Like McConaughey, Renée Zellweger makes her screen debut in this film in a tiny, uncredited part. Her presence, I can only assume, goes unnoticed because of her physical resemblance to Joey Lauren Adams, who had the meatier (and credited) role of Simone.

As I recently wrote in these digital pages, Dazed and Confused is the film “that best approximates what my high school years in late 90s Georgia were like.”

Growing up, my county was “liquor dry,” so the only Mexican restaurant in town made frozen margaritas with white wine instead of tequila. To purchase the harder stuff, one had to drive to the county line. It was a service that I, with my aforementioned fake ID, sometimes provided to my friends for a small fee.

TripAdvisor lists McKinney’s as the #1 (of 1) restaurant in all of Midville. But the joint was , and likely still is, legitimately delicious.

Okay, yes. Don does subsequently break this moment of sincerity by concluding “I dogged as many girls as I could while I was stuck in this place” to riotous laughter from those assembled. On the charge of crimes of omission, I plead guilty.

You've penned a vividly poignant essay, Justin. It was lovely to read about your Waynesboro experiences in the context of this iconic film. As a fellow film fanatic, this was a delight.

Keep it up! Now I'll be looking forward to reading more of your work! ;)